CLOSINGS

When to End Negotiations

Learning Objectives

Est. time: 12 min.

- Deciding when continuing to negotiate is not worth it

- Analyzing the costs and benefits of pressing for more

- Balancing the potential risk and reward of making a take-it-or-leave-it offer

How you can participate

- Use the comment tool at the end of the module to add your insights and questions

- Engage with fellow learners and share your best practices

- Check regularly for comments from the creators of Negotiate 1-2-3

Introduction

When are you done negotiating? Despite you and your counterpart’s best efforts, you seem to be at impasse. The question for both of you is whether to continue the process or abandon it. A similar choice can arise in situations where you’ve already received an acceptable proposal, but still must decide whether to accept it or push for more. In both instances, you have to compare what you expect to achieve through further negotiation with how you likely will fare by walking away.

In negotiation terms, it’s the classic BATNA concept. You weigh what your counterpart is willing to accept against your best-alternative-to-a-negotiated-agreement. If you have good options, then their proposal will have to be even better. If your alternatives are poor, you may have to live with much less. It is basic decision analysis, choosing whether to go down one path or the other. All things considered, which is better: deadlock or a deal?

Your BATNA is a course of action—what you would do—not a dollars and cents bottom line. As you consider its pros and cons, subjective factors—even moral ones—may come into play. For example, you might happily sell your old car to a cousin for $5,000 even though you know a stranger would pay a lot more. In short, price is just one consideration in calculating your walkaway.

The concept is simple. Applying in practice, however, is more complicatedthan simply weighing your options at the present moment. There’s almost always a degree of uncertainty about whether your position will get better or worse. Your counterpart might improve her latest offer or withdraw it. Likewise, your nonagreement options may improve or deteriorate. The examples that follow will help illustrate these concepts.

Deciding to Walk Away

Let’s say an agent for a hockey player is negotiating with the general manager of his professional team. The parties seem to be at an impasse. The GM has offered $3 million annually for a long-term contract. The agent insists on $4 million. He has in hand a $3.5 million offer from another team, so there is a big gap between the two offers.

A week has passed and neither side has made a concession. Should they just shake hands and go their separate ways? After all, not everything is negotiable. This may be case where there simply isn’t any room for agreement.

But it’s also possible they could still reach a deal. The stalemate may be temporary. The GM may think the agent is bluffing. Nobody else has offered the player $4 million. And his own team is a strong contender to win the league championship. The GM thinks, the player must recognize the value of that opportunity. On the opposite side of the table, the agent may be convinced that the GM is just playing hardball and will ultimately improve his offer.

This could be a situation where each side is stubbornly waiting for the other to blink. It’s also possible that neither is willing to budge. Whichever is the case, prolonging a fruitless negotiation could be costly. It’s not just the wasted time. While talks drag on, the team could lose the chance to sign another good player. Likewise, the player runs the risk that the other team may withdraw its $3.5 million offer.

When there is a gap between your best offer and the other side’s demand, the question for both of you is whether the upside of continuing the process is greater than the downside of calling it quits. For negotiation to continue in the face of seeming stalemate, both two parties must believe there’s still potential room for agreement. On the other hand, it only takes one pessimist to bring negotiation to an end.

There are no crystal balls for negotiation. Whatever the assessment—positive or negative—it may be wrong. Sometimes hopeless negotiations drag on too long. In other cases, people abandon talks when just a little more brainstorming could have benefitted everyone. (The module on Creativity in this unit offers examples.) External factors may change as well, transforming what originally seemed like an unacceptable outcome into one that the parties can live with.

There are times, of course, when cutting your losses is wise. Beware of wishful thinking. Don’t snare yourself in a sunk cost trap by wasting time in a hopeless effort. If you aren’t close to reaching agreement now, ask yourself what must change and how likely that is to happen.

Walking away doesn’t necessarily mean failure. In fact, if you are never deadlocked, that’s a worrisome sign. It can only mean one of two things, and neither of them is good. A 100 percent agreement rate suggests that you may sometimes say yes simply for the sake of closing the deal, even when you’d be better off doing otherwise. Or, if that’s not the case, you’re likely too cautious and only go after sure things. Sometimes pursuing a longshot makes sense if the possible payoff would be sufficiently high.

When deciding whether to abandon the negotiation process or plow ahead, consider your general temperament. Persistence is often a virtue, but stubbornness is not. On the flip side, if you sometimes get discouraged, make sure that doesn’t color your assessment of what could lie ahead. Whichever the case, before breaking off negotiations remember to:

- Give your counterpart notice that you’re prepared to walk way. They may decide to improve their offer.

- Be clear about what you need from them in order to say yes to a deal.

- Do what you can to preserve the relationship. Who knows—you may work with this party again.

How Good is Good Enough?

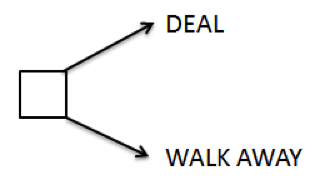

Some negotiations that take time eventually produce acceptable deals. The outcome might be something that you could merely live with. Other times, it could be more than you initially hoped for. the latter case, you might be tempted to snap up the offer, but you could be leaving some value on the table. The choice here isn’t about accepting the offer or walking away. Rather it’s between taking it or pressing for something even better. That adds another branch to your decision tree.

If you are very lucky, once in a while you may get a spectacular deal without having to push at all. In the early 1970s, teams in the fledgling World Hockey Association were trying to gain credibility by luring big-name players from the long dominant National Hockey League. The Philadelphia Blazers had their sights on Derek Sanderson, a former NHL Rookie of the Year and flashy center on the Boston Bruins.

Sanderson was happy where he was but felt there’d be no harm in finding out what he was worth on the market. He was currently earning $75,000 a year from Boston. The Blazers offered him $2.3 million for three years. “I was stunned,” Sanderson remembers.

A friend he had brought to the meeting with him whispered, “Take it. Take it!”

But Sanderson just sat there,“we could make that $2.6 million,” the general manger said. “That’s when I knew I had them,” Sanderson now recalls.

Still, he didn’t accept. Instead, he said, “It would be awfully hard to leave the Bruins. It was my lifelong dream to play in the NHL.”

The Blazers’ offer jumped to $3 million, and Sanderson still wasn’t done. “I’ll need a limo for my girlfriend, of course,” he added. The team said yes to that and even agreed to hire his father as a scout.

Sanderson finally ran out of asks. He signed a deal that made him the highest-paid pro athlete in the world at the time, even topping Pelé, the legendary Brazilian soccer star. Was Sanderson smart in pressing for more, or just lucky that he didn’t exasperate Blazers' management to a point where it would sign a better player for far less money?

Sanderson’s story is really about the team negotiating against itself. The managers took his stunned silence as steadfast resolve. They were so eager to get a yes that they kept improving their offer. Usually, however, if you want to get more, you have to for it. Then the challenge is knowing how much to ask for and when to stop asking.

It’s a matter of balancing risk and reward. The harder you press, the more you may gain—but also the more you stand to lose. Decision-making models ostensibly locate the crossover point where the net payoff becomes negative. Such formulas aren’t much practical use in real negotiation, though, since estimates of messing up a deal are only rough guesses. With some items there may be no harm in asking, while others shouldn’t even be broached. In between those extremes, however, the pros and cons will be fuzzy.

It’s safe to start from the premise that whatever you’ve been offered, you can likely do better. That’s not always true, but it’s a fair bet. It’s possible—but not probable—that you’ve magically landed on a package that is the absolute best that your counterpart can do for you. It’s also possible—though not certain—that there are no further ways to expand the pie through creative trades.

The only way to know for sure how far you can go without blowing up a deal is by going a little farther than that. Short of that point, you’re operating in a gray area. It’s like driving on the interstate. If the posted limit is 65 miles an hour, you almost certainly can go 68 without getting ticketed. You’re probably okay at 72 as well, though you should keep your eyes open for patrol cars. At 75 or more, you could be pushing your luck.

A couple of years ago a colleague of mine was being wooed by a well-regarded university (not my own, incidentally). We’ll call him Ben Evans to spare him embarrassment. Ben was flattered that Arundel University (also a pseudonym) was interested in him and excited about the prospect of moving back east.

There still were some issues to be worked out, though. Arundel’s usual practice was to have lateral hires come in as visitors for a year before being given a permanent position. “Sorry,” said Ben, “but you know my work well and I’m not comfortable with being on probation.” Arundel made an exception and agreed to grant him tenure right from the start.

Then there was salary. Arundel’s scale was lower than he had expected. Ben pushed hard for the upper end of the range and won that, too. Getting an increase in his research budget proved more difficult, but he made headway there, as well.

“Are we all done?” asked the dean after that was resolved.

“Just one more thing,” said Ben. “This is a big move for my wife and me. She’ll have to wind down her present job and find something new near Arundel. We’d like to delay our arrival for a year.”

There was silence on the other end of the line and then the dean said, “Let me get back to you on that.”

That was around noon on a Wednesday. Thursday came and went. Late Friday morning the doorbell rang. Ben signed for a FedEx delivery and then opened the white cardboard mailer. Inside was a standard business size envelope that contained a two-sentence letter.

Dear Professor Evans,

We are withdrawing our offer for a faculty position at Arundel University. We wish you well in your academic career.

Yours truly,

Dean J. Joseph Gibson

Ben was stunned. Everything had gone so well, with Arundel agreeing to most of what he’d asked for. And for him, the start time wasn’t a deal-breaker. He just wanted to raise the issue. If being on board this coming September was that important to Arundel, he’d find a way to manage it. Why didn’t the dean just say no?

Ben phoned a friend on their faculty and asked how he could salvage the deal. It’s over, Ben,” the friend said. “I tried to stick up for you, but people have moved on. As somebody else put it, if you were like this during courtship, marriage was going to be hell.”

Knowing where to draw the line is tricky in negotiation. Whatever signs are posted are hard to read and may be in a language that’s difficult to grasp. Ben spoke to the dean long-distance, but even if they had met face-to-face, they still could have been far apart in respect to what was said and what was meant. Ben felt that he was floating practical questions. No harm in asking, he told himself. On the other end of the line, however, his inquiries sounded like demands, each one more presumptuous than the last. I know Ben to be a good guy and great to work with, but that’s not how he came across in the negotiation.

Ben admits much of the blame for killing the deal lies with him. But the dean bears responsibility for the stalemate, too. He may have been shocked by Ben’s audacity. Perhaps he’s someone who has trouble saying no. Ben heard the question “Are we done?” literally, taking it as invitation to add yet another demand to the mix. But the dean may have meant, “Watch it, my friend, you’re testing my patience.” Ben was treading close to the edge but missed the subtle warning.

Effective negotiators send clear signals about what’s acceptable and what is not, especially in the critical closing moments. When the dean agreed to increase Ben’s research budget, all that was needed to save the deal would have been adding, “But that’s it. Understood?” Because that wasn’t explicit, however, a potential win-win proposition was lose-lose for both sides.

Risk Tolerance

Here is a one-question quiz, a parable of sorts, to test how you view the upside and downside of pressing for more when you already have already received an acceptable offer from your counterpart.

Summary

Closing a negotiation isn’t only about what you ask for. It’s also about how you ask for it. If people feel that they have been disrespected or treated unfairly, they may turn down an offer that’s substantively superior to their no-deal alternative. The stalemate in Ben Evans' negotiation with Arundel University was due at least as much to communication problems as it was to terms. After all, the University had already put an offer on the table that Evans was satisfied with.

The next module in this unit—Barriers to Agreement—deals with interpersonal and process problems that can derail agreement. Later modules on Persuasion; How to Say Yes; and How to Say No complement the analytic focus of this module. For now, remember the following:

- Walking away from the bargaining table does not mean you failed.

- • Monitor your progress. Are you gaining a better understanding of your counterpart’s interest? Do they have a better understanding of your needs? Are you developing an effective working relationship? If your answers are no, then take a hard look at whether continuing the process is worthwhile.

- Just because you have received an acceptable offer doesn’t mean you should stop negotiating.

- To conclude a negotiation smoothly, begin that same way.

Resources

Deepak Malhotra and Max Bazerman, Ch. 13 "When Not to Negotiate," Negotiation Genius, Bantam, 2008.

Derek Sanderson, Crossing the Line: The Outrageous Story of a Hockey Original, Triumph Books, 2012.

Michael Wheeler, Ch. 9 "Closing," in The Art of Negotiation: How to Improvise Agreement in a Chaotic World, Simon & Schuster, 2013.