CRITICAL MOMENTS

Agility

Learning Objectives

Est. time: 20 min.

- Understanding the importance of strategic and tactical agility in negotiation

- Formulating realistic plans in the face of uncertainty

- Recognizing and capitalizing on unanticipated opportunities

How you can participate

- Use the comment tool at the end of the module to add your insights and questions

- Engage with fellow learners and share your best practices

- Check regularly for comments from the creators of Negotiate 1-2-3

Introduction

Master negotiators are agile strategically and tactically. Their plans are flexible, subject to change depending on unexpected twists and turns. These negotiators also are quick on their feet moment-to-moment, so they can respond effectively as events develop.

Their success rests upon embracing the reality that negotiation can't be scripted. Preparation is important, but negotiation is always a two-way street. Whoever sits across the table from you may be just as smart and determined (and fallible) as you are. You can't dictate their agendas, attitudes, or actions any more than you'd let them determine what you say and do.

Adaptability is imperative in negotiation from start to finish. Opportunities will pop up. So will obstacles. Power ebbs and flows. Talks that crawl along can race forward or veer off in another direction. Even our own objectives may evolve. You must be ready for surprises and make the best of whatever transpires.

Donald Dell, the pioneering sports agent/marketer, knows this very well. (You may remember him if you've seen the Outburst module in this unit.) Dell made his mark by hammering out huge contracts for basketball players Patrick Ewing and Moses Malone, and earning millions in endorsement deals for tennis stars Arthur Ashe and Jimmy Connors. He even orchestrated bidding wars between rival television networks for broadcasting rights to events like the French Open.

Dell has also done very well negotiating on his own behalf. In 1998 he sold his sports management firm, ProServ, to an entertainment company for an amount he describes as "the proverbial offer I couldn't refuse." A few years later, after buying much of it back for twenty cents on the dollar, he then resold his interest to Lagardre Unlimited, where he is group president in charge of TV deals, events, and tennis. For all his success, though, Dell is quick to say that things often don't go according to plan.

In his book, Never Make the First Offer (Except When You Should), he writes: "I can't tell you how many times I arrived prepared for a negotiation, only to have someone or something come up that upset or changed the deal I thought I was doing. The only way to protect yourself 100 percent against this situation is to assume there is something you don't know. This advice will not only keep your mind up to speed with the deal and force you to consider other parties' motivations, but it will also keep your ego in check."

United Nations special envoy Lakhdar Brahimi describes the special mindset this requires. Brahimi speaks from impressive experience, having mediated in some of the world's most volatile trouble spots. Succeeding in turbulent situations requires "navigating by sight," as he puts it. He acknowledges that preparation is important, but so is letting go of expectations in order to deal with unanticipated obstacles and opportunities.

You can hear him describe that balance at a conference in which he was given the Great Negotiator Award by the Program on Negotiation (an interuniversity consortium, based at Harvard Law School. He begins, by referring to Roger Fisher, co-author of the classic text, Getting to Yes: How to Win Agreement without Giving In. Watch the video clip below.

So you take all the books of Professor Fisher, you read them, understand them if possible, but I am sure Professor Fisher will agree that in his map maybe he will have missed one little rock somewhere on the sea will be navigating in and to spot that rock, and you have got to use your eyes, that's the only instrument that will show you because the map contains, you know, all the ocean, everything, except that little rock. So this is the navigation by sight. That is really another way of saying keep an open mind and be ready to change and adapt to the situation. Don't ask reality to conform to your blueprint but transform your blueprint to adapt to the reality.

Lessons from military doctrine

Negotiation dynamics have much in common with warfare. At first glance, that may seem like a peculiar match. The stakes are entirely different in battle, of course, and our counterparts in negotiation are seldom enemies. (Indeed, they often are colleagues or long-term business partners.) But negotiation and warfare are similar in at least one important respect: both take place in an atmosphere of high uncertainty.

Two centuries ago Prussian military strategist Carl von Clausewitz coined the term "fog of war" to capture the fluid and uncertain nature of armed conflict. It remains central to military doctrine today and could just as well describe the terrain in which negotiation unfolds. Consider this excerpt from the United States Marine Corps' current Warfighting Manual. For our purposes it has been slightly modified. In place of belligerent terms (like war, battle, and enemy), neutral terms like "negotiate" and "counterparts" have been substituted. These changes are shown in bold.

All actions in negotiation take place in an atmosphere of uncertainty, "the fog of negotiation." Uncertainty pervades negotiation in the form of unknowns about counterparts, about the environment, and even about the friendly situation. While we try to reduce these unknowns by gathering information, we must realize we cannot eliminate them - or even come close. The very nature of negotiation makes certainty impossible; all actions in negotiation will be based on incomplete, inaccurate, or even contradictory information.

Take a moment to re-read the last phrase. If you recognize that actions in negotiation will often be based on incomplete information, then the need for agility becomes paramount. As you will see in this module, agility is as much a mindset as it is a specific skill. Maintaining that outlook compels negotiators to craft strategy that takes into account the various ways counterparts may respond (positively or negatively), as well as the chance that circumstances may change, for either better or worse.

Navigating by Sight

General Dwight Eisenhower famously said, "Plans are worthless." That may seem like an odd statement coming from the architect of the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944, who marshalled the largest battle force in history. But there's an old military adage that "plans go out the window at first contact with the enemy." Equipment can fail. The enemy may be more entrenched than expected. Weather can turn foul. Success can rarely be guaranteed.

Nevertheless leaders (and negotiators) must move forward despite uncertainty. Leaders, in particular, have to express public confidence that they will prevail, even though they have private doubts. Addressing Allied troops bound for the beaches of Normandy, Eisenhower said, "You are about to embark on the great crusade. The tide has turned! The free men of the world are marching to victory!"

In spite of his professed confidence and the unprecedented planning and preparation, Eisenhower knew that victory was far from assured. In his pocket were notes for a statement he was ready to make if the Allied troops were beaten back. It read:

"Our landings in the Cherbourg and Havre area

have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold, and I have withdrawn the

troops."

"The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion

to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt, it is

mine alone."

The same kind of best-case/worst-case thinking is essential in negotiation. When the stakes are high, however, it can be difficult to accept that things may not go as well as you hope. But that realism is imperative to making the best of a bad situation. Confidence and optimism are essential, but they must be coupled with clear-eyed recognition that omniscience is never possible in negotiation and that luck won't always be with you.

To put it another way, the trick is to have a plan, but not let the plan have you. That doesn't mean just waiting to see what happens and making things up as you go along. Eisenhower didn't trust concrete plans, but he was quick to add that "Planning is everything." That may sound paradoxical, but in his terms, a plan is a rigid set of instructions, not to be altered. Planning, by contrast, is an active and ongoing process that reveals a range of possibilities and choices accompanying each.

The distinction applies in negotiation, as well. Good planning involves identifying provisional goals and envisioning alternative routes for achieving them. But just as Lakhdar Brahimi cautions, you must be alert for uncharted rocks along the way. It is easy to fall in love with your plan. Don't ignore signs that that it's time revise or discard it. Instead, as Brahimi says, "Transform your blueprint to adapt to the reality."

Agility in business negotiations

Part One

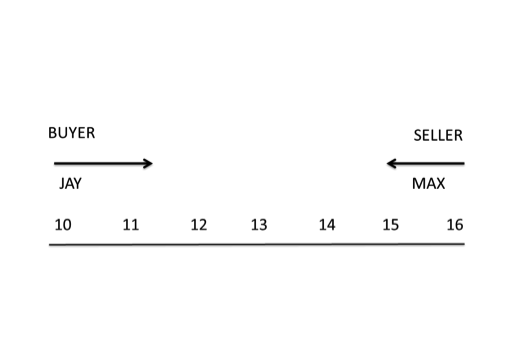

Jay Sheldon, a director of a private investment firm, bought a small cable television company in the Midwest some years ago. He didn't know much about the industry, but the $8 million price seemed right, and the purchase would let him test the water. Whatever risk might be involved was tempered by the fact that the deal was leveraged.

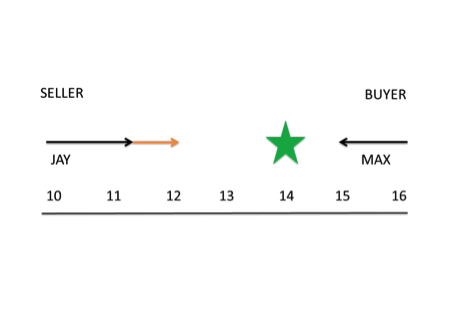

Jay and his partners quickly got the business into the black. A year later, they wanted to expand by acquiring nearby systems. After running the numbers, they figured that they could pay $11.5 million to buy a second cable company in a neighboring city. Given the potential economies of scale, they might go to $12 million, but that was absolutely their upper limit.

Jay began an extended series of talks with its owner, a man named Max, but after two months of back-and-forth, it became obvious that the parties were far apart on price. "Listen," Max finally said, "I didn't post a For Sale sign. You came to me. You'd have to dump fifteen million in cash right on my desk to tempt me. And I'd probably kick myself if I took it."

Jay understood that this wasn't a bluff, but he also felt the demand was unrealistic. By conventional logic, the parties were $4 million dollars apart.

Even if Jay swallowed hard and increased his offer to $12 million, there still would be a big gap. What could he do to conclude the deal?

Part Two

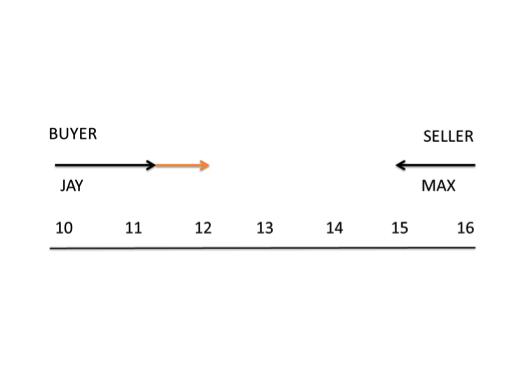

"Let me ask one last question," Jay said before getting up to leave. "If you think your system is worth fifteen million, how about ours?"

"Oh, yours is a bit smaller," was the answer. "I'd say fourteen or so."

Jay quickly turned the deal upside down. He adroitly became the seller instead of the buyer. After a little more than a year, he flipped his own system for almost twice what his firm had paid for it (and much of that had been leveraged). He was still bullish on cable, but when he encountered this particular owner, who was rabid about the industry, Jay had the agility to transform an apparent impasse into a lucrative sale.

His solution was clever. More important, though, was his nimble mindset. In the impediment to his hoped-for acquisition, Jay spotted the seed of a deal that would serve him even better. When he let go of his initial plan, the insight arrived in a flash.

He succeeded because he did exactly what Brahimi advises: he adjusted his plan to conform to reality.

Cookie-cutter strategies crumble in the turbulence of real-world negotiation. Jay was intent on buying the nearby cable system. When it became clear that its owner wouldn't budge on price, however, he didn't try to beat him down further or cave on his own valuation of that business. Nor did he walk away. Instead, he adapted by crafting a superior Plan B. But remember that it was Jay's agility that made it all happen. His counterpart, sitting at the same table, looking at exactly the same facts, didn't imagine being a buyer until Jay proposed it.

Seizing Opportunity

We'll return to Special Envoy Lakhdar Brahimi again for more insight about agility. At the conference in which he one his Great Negotiator Award, he fielded questions from panelists and the audience. He has an easy conversational manner and he would begin his answer by saying, "Well, let me tell you a story." Because much of his mediation work has taken place in war torn areas, his stories are memorable.

One panelist asked him he knows when a negotiation is hopeless, and he needs to walk out. Brahimi reached back decades when he was trying to broker peace in a bloody civil war in Lebanon. Here, in his own words, is how he described his thinking (and his luck) in facing a critical moment.

"In Beirut, the first cease-fire worked out was on a day that was absolutely horrible. Bombs were falling all over the place and as you know there was just artillery shelling indiscriminately. And I went, you know Beirut from the Somerland in the west to Banda, the president's palace where General Aoun was sitting, I didn't see one human being, one cat, one dog, because of the shelling. It was really hard. And when I arrived there and started talking to General Holm, bombs were actually falling on the palace. So after talking, he said look, I'm going to give you an armored car, the army point to see what is happening. So I told him, OK if I go away, do you have anything to do? He told me no. I said why don't we talk a little bit more then? Why did I do that? I think I was afraid to drive back. But then I think this is the reason why I stayed. But that additional discussion we had produced the cease fire. It was I think on a Saturday and Beirut being what it was I think the end of the morning, by the evening people were out eating in restaurants and so on. That cease-fire did not hold. This is when to stay and when to leave. It was stupid enough to drive to Banda in the first place under those shells. To drive back would have been too much. So better try and work for a cease-fire."

It is hard to imagine a more harrowing situation than being under attack in a battle zone. Yet, notwithstanding the danger (and despite his own fear) Brahimi used the moment to broker a temporary ceasefire. A few hours later, the streets of Beirut were alive with people getting back to their normal routines. Conditions that evening would have been very different if he hadn't extended his discussion with General Aoun.

For Brahimi, "navigating by sight" isn't just being alert for unmarked reefs that could sink your ship, but also recognizing unexpected opportunities that may pop up, as they did for him in this case. It's an ongoing process of appraisal and reappraisal, and it requires comfort with uncertainty and change. Frank Barrett, author of Yes to the Mess: Surprising Leadership Lessons from Jazz, who teaches organizational behavior at the Naval Postgraduate School, calls this having an "appreciative mindset." The more challenging the situation, the more important is cultivating this outlook.

Barrett doesn't mean appreciation in the sense of liking or gratitude, but rather it's an understanding and acceptance of one's current situation. As he puts it, having this type of mindset means "saying yes to the mess." For negotiators, it means playing as best you can whatever cards you're dealt, rather than fretting about getting a bad hand. It also means understanding that sometimes an apparent obstacle can present a new opportunity (just it did for Jay Sheldon in his cable TV deal).

Summary

We negotiate with others in hopes of finding an outcome that is superior to anything we can achieve unilaterally. (Otherwise there would be no need to get assent from other parties.) Two companies reach agreement when, all things considered, the terms that they reach are better than either of them can get elsewhere. Litigants resolve their differences, when, and only when, each party sees settlement as superior to taking the chance of going to court.

Whether you reach agreement and what specifically you agree upon, however, is not just up to you. Your counterpart will have their own ideas about what issues must be addressed and how the negotiation should proceed. If they're reasonable and creative, you will head down one path. If not, you could be on a much rockier road.

Practical planning takes such possibilities (and more) into account. It exposes what you don't know and must uncover during negotiation. It encourages you to think contingently about choices you may face, depending on how things play out. Sometimes you may have the luxury of brainstorming elaborate, robust plans that take into account a range of scenarios from worst to best, with others in between. Other times you may have limited time to think before you act. When that's the case, borrow a practice of the US Marines. In the first wave of an attack, when they encounter unexpected conditions and have limited time to plan, they focus on two questions:

- What is most likely to unfold; and

- What is the most dangerous thing that could happen?

Those two alternatives don't include all the possibilities, but they do cover the most important territory. And they open your eyes to possible surprises.

If you're negotiating to extend a contract with an existing customer, for example, a reasonable place to start is looking at the current deal. But it would be wise to consider dangers, as well. What if the customer claims to have found another supplier who will beat your price? Or what if you learn that the company is struggling financially? It isn't pleasant to imagine such situations. But it's better to be prepared for adversity than to be blindsided by it.

In short:

- Set provisional goals but revise them when circumstances don't play out as expected.

- Bake agility into your plan by anticipating best- and worst-case scenarios.

- Don't fall in love with your plans.

Resources

Frank Barrett, Yes to the Mess: Surprising Leadership Lessons from Jazz, Harvard Business Review Press, 2012.

Donald Dell, Never Make the First Offer (Except When You Should), Portfolio, 2009.

Roger Fisher, William Ury, and Bruce Patton, Getting to Yes: How to Win Agreement without Giving In, Penguin, 1981, 1991.

Gary Pisano and Francesca Gino, "Why Leaders Don't Learn from Success," Harvard Business Review, April 2011, 68-74.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and in the Markets, Random House, 2008.

U.S. Marine Corps, Warfighting Manual, MCDP-1.

Michael Wheeler, Chs. 4 "Plan B" and 7 "Situational Awareness" in The Art of Negotiation: How to Improvise Agreement in a Chaotic World, Simon & Schuster, 2013.