OPENINGS

Setting the Stage

Learning Objectives

Est. time: 20 min.

- Weighing the costs and benefits of negotiating on your own turf

- Dealing with multi-party teams

- Positioning yourself to be persuasive

How you can participate

- Use the comment tool at the end of the module to add your insights and questions

- Engage with fellow learners and share your best practices

- Check regularly for comments from the creators of Negotiate 1-2-3

Introduction

Step one in negotiation is convincing your counterpart to engage with you about a possible deal. Often this is routine. If you’re shopping for a car, you know to go to dealership that sells them. Likewise, people who put a For Sale sign on their lawn are eager for buyers. As we saw in the previous module (Getting Them to the Table), however, gaining another person’s attention sometimes is a challenge.

Even when that’s resolved, there’s the matter of setting the stage: deciding on where to meet and who will be involved. This can be routine, as well, but sometimes it’s contentious. When parties can’t agree on the process, negotiations come to a halt—before they really can begin—at least until people’s attitudes or circumstances change.

To explore such issues and analyze some cases, complete a short survey about your own feelings about negotiation ground rules.

Where to Meet

Those two survey questions are taken from a longer questionnaire on available on HBR.org, Assessment: What Kind of Negotiator Are You?. Later, when you’re finished with this module, you can see how other tactical decisions reflect your general approach to negotiation. First, though, let’s consider cases where how situational factors had an impact on important diplomatic and business negotiations.

Here are results from the 14,000 people who took the HBR survey:

- When possible, I negotiate on my own turf - 20%

- I prefer a neutral site where no one has an advantage - 20%

- I like to negotiate where the other side will feel most comfortable - 26%

- It makes no difference where I negotiate - 34%

In short, a third of the respondents feel it doesn’t matter where they negotiate. The flip side of that is that most people think it does, though in different ways. Forty percent favor their own domain or a neutral site. That reluctance may be about maintaining their own comfort and control. Or it might be worry about symbolism, not wanting to look like they made a concession or are desperate. Then again, extending oneself to make the other side feel comfortable could be a positive if it’s interpreted as a good will gesture and it’s reciprocated. Of course, that’s not always guaranteed.

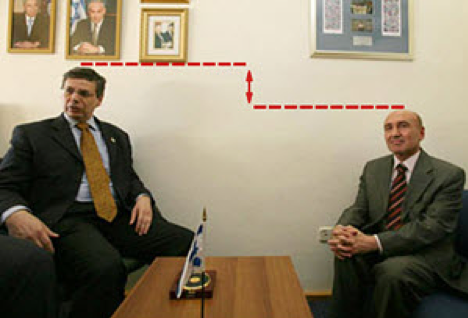

In 2010 an Israeli Deputy Minister summoned the Turkish ambassador to rebuke him for a television series that had been airing in the latter’s country. As you can see in the picture, the host situated himself in a taller chair and put his guest in a lower one. (He also removed the Turkish flag from the table, violating a customary courtesy.)

Whatever the Minister’s intention, his game of chairs backfired badly. A photo of the meeting was published worldwide and the Israeli host was roundly criticized for trying to demean his counterpart. The relationship between the Israel and Turkey, already tense, worsened significantly.

Hardball tricks like this run counter to the advice in the classic book Getting to Yes. Its authors—Roger Fisher, William Ury and Bruce Patton—counsel negotiators to “separate the people from the problem.”

Their view is pragmatic and based on the notion that the tougher the substantive issues, the more important is not getting sidetracked by petty squabbles. They advocate arranging the setting to foster collaboration, not confrontation. As they state, “It helps to sit literally on the same side of a table and to have in front of you the contract, the map, the blank pad of paper, or whatever else depicts the problem.” Where possible structuring the negotiation as a “side-by-side activity” encourages the parties to “jointly face a common task.”

There are times, however, when stage setting isn’t just about one-upmanship. Instead it may be bound up contentious issues that are up for negotiation. The Paris peace talks that brought the Vietnam War to a close were delayed for months while the parties fought over the shape of the table. Many observers were outraged at having hundreds of soldiers and civilians perish daily because of debate over furniture placement.

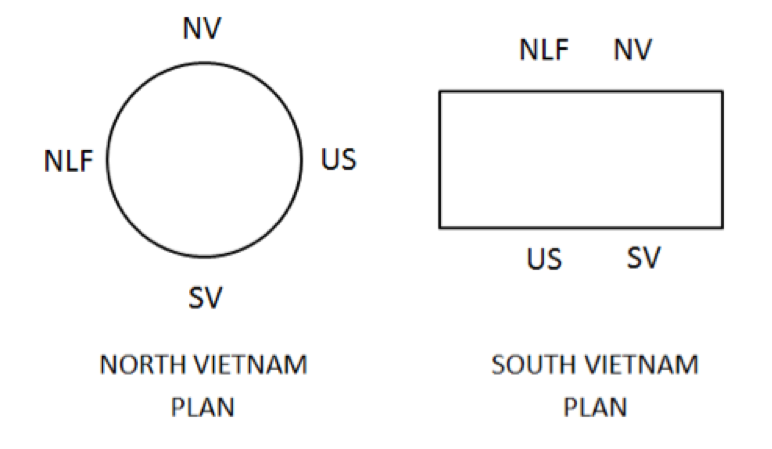

Much more was at issue, however. North Vietnam and its ally, the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (also known as the Viet Cong or NLF), refused to recognize South Vietnamese government. South Vietnam, in turn, would not recognize the NLF. The issue of legitimacy was central to the conflict.

North Vietnam insisted on a circular table where all four parties would be accorded equal status. Countering that, South Vietnamese officials insisted upon a rectangular table where it would sit next to the US representatives. Opposite them would be North Vietnam and the NLF.

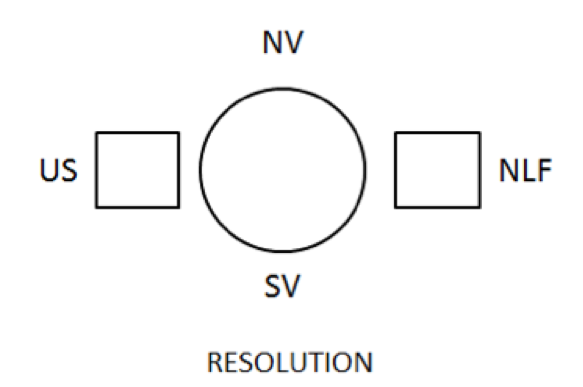

After months of stalemate, chief American negotiator Averill Harriman proposed an arrangement that would allow NLF representatives to be seated near the North Vietnamese team, without being acknowledged by the South Vietnamese. In turn the South Vietnamese government could be seated near the American delegates without being formally recognized by the North Vietnamese.

In the face of this dispute, what setup would you have proposed? Consider that for a moment, then click the button below to see what ultimately proved acceptable to the four parties.

This three-table design allowed each party to assert that it hadn’t buckled to its enemies’ demands. In practice, though, the U.S. representatives would often move over to consult with their South Vietnamese allies. Likewise, the NFL leaders would huddle with representatives from North Vietnam.

We can never know whether the deadlock would have been broken earlier if this proposal had been made at the outset. Additional factors may have prolonged the stalemate. But once the parties had locked themselves into a particular design (the circle or the rectangle), it’s unlikely that either side would have accepted the other’s idea. At the very least, Harriman’s solution was a successful face-saving device.

Who's Invited?

Now we’ll shift to another element in stage setting, settling on who will take part in the discussion. In the short survey earlier in this module, you were asked how you feel about being outnumbered at the bargaining table. Again, opinion was divided. Here are the results:

- I feel at a disadvantage if the other side brings a larger team to the table. - 35%

- I often find that being outnumbered actually benefits me. - 20%

- It doesn’t matter much if I’m on the bigger team or the smaller one. - 44%

As you can see, a plurality didn’t care about being on the larger or smaller team. Somewhat more people felt it mattered, with most of them preferring being on the bigger team by 35% to 20% margin.

There are arguments for each viewpoint, though much depends on circumstances. In complex negotiations, including people with expertise in different areas—for example, finance, law, and technology—may be essential. The bigger the group, though, the more difficult internal coordination becomes. Team members need to speak with one voice. Private caucuses may be necessary to share impressions and adjust strategy depending on how the discussion across the table is going.

A smaller team has the advantage of agility. When you’re on your own, across the table from a big group, you need to be poised and aware of factions on the other side. That takes emotional intelligence and stamina. The next short video tells the story of a negotiator with an abundance of all those resources.

Summary

Donald Dell’s story reminds us how the stage can shift during negotiation, sometimes a little, sometimes a lot. Unexpected issues may pop up and new players may burst onto the scene—as the CEO did in the Head tennis racquet case. Like a good improv actor, Dell adjusted to the situation and stood his ground in a way that didn’t alienate others at the table.

One last point about stagecraft in negotiation. Even if you’re not the director or the star, it’s important to choose a role and a spot where you’ll maximize your influence. According to psychologist Robert Cialdini, it’s not just what you say that makes you persuasive. It’s what you do before you speak that matters most. That’s the core message of his book, Pre-suasion.

Here’s an example he offers. Imagine you’re walking into a meeting that will either approve or reject an important project you're proposing. Your boss has clearly stated that she will make the final call, but first she wants to hear the views of others in your group. Some colleagues support your initiative. Others don’t.

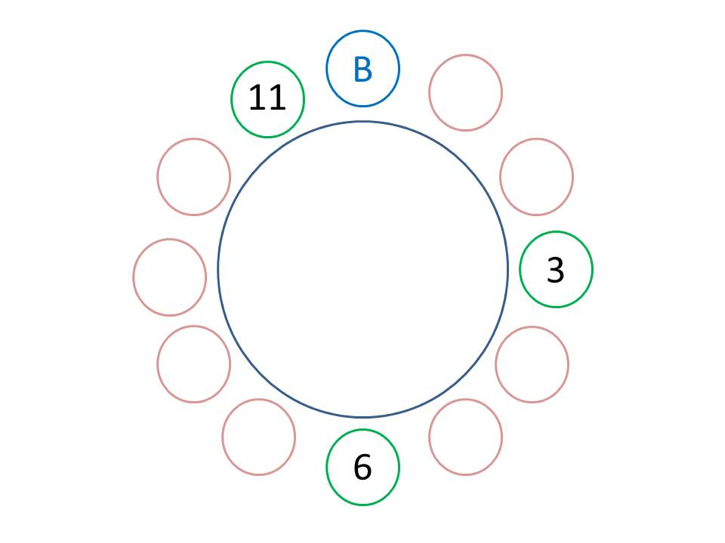

You’ve arrived a few minutes early, but most of the dozen seats are already taken. Your boss is settling in at the 12 o’clock position. All the red seats are filled. The only ones left are at the 3, 6, and 11 spots.

The boss likes to get everyone into the discussion. Starting a meeting, she typically does a check-in, going clockwise around the table, leading off with the person immediately to her left. Each person has one minute to state an opinion or to pose a question.

You have only a couple of seconds to make a choice. To wield the most influence, where’s the best place for you to sit? Cialdini has a strong point of view on that question. Now that I’ve heard it, I think he’s right. Before revealing his answer—and the reasons for it—please take a moment to consider it yourself.

I posted this puzzle on my LinkedIn negotiation blog. It drew 46,000 views and sparked many comments. An accompanying survey found opinion sharply divided on which is the best seat. Here are the results:

- 3 o’clock - 25%

- 6 o’clock - 36%

- 11 o’clock - 37%

- It doesn’t matter - 2%

Three things are striking. For starters, almost everyone thinks the choice matters. Second, there’s no consensus on why it does! Here are arguments that people made in favor of the various options.

The case for 3 o’clock. Some people liked the idea of letting the discussion get started, before jumping into the conversation. They could listen to and respond to a couple of colleagues, but then have the chance to influence what eight others would say.

Reasons for 6 o’clock. Other respondents wanted to speak up mid-way, balancing the value of listening to some people, while preserving the chance to impact what others may say. Having the best view of the boss and being able to look her in the eye was also recognized as beneficial.

The case for 11 o’clock. People choosing this chair believed that having the last word would be an advantage. That sounds reasonable, too. All other things being equal, the opportunity to address people’s concerns and objections can be a plus. But other things may not be equal in this situation.

Now, since I've listed credible reasons for all three of the options, it might seem as if I’m leading up to a “it doesn’t matter” conclusion. Far from it. If given the choice between 3 and 6, I personally prefer the latter because it allows direct engagement with the boss, though I wouldn’t be uncomfortable sitting in 3. Robert Cialdini would say that that may be right, but it’s for the wrong reason.

Remember that I said earlier that three things about the survey results and comments are striking. The third is that almost nobody mentions the most important factor to consider whenever you want to be persuasive: It’s making sure you have the full attention of the person you’re trying to influence.

In Pre-suasion Cialdini says that in scenarios like this one, seat 11 is to be avoided at all costs because of what he calls “the next-in-line effect.”

Here’s why. Even if you are eloquent and you deftly build on what your allies say about the project (and debunk any skeptics), your boss won’t be listening if she’s in line to speak next. Instead, she’ll thinking about what she’s going to say herself. She’ll be in what Cialdini calls a “self-focused bubble.”

If you have doubts on that score, just recall where you mind goes when you’re next on the agenda to step to the podium or about to give a presentation. You’ll be absorbed in what you’re about to do, understandably so. Whatever the person immediately before you says will be background noise at best.

Here is Cialdini’s big point. Being persuasive isn’t just about crafting what you plan to say. It’s about getting out of your own head and into the mind of the person you must convince. Make your pitch when—and only when—they can be focused on you, undistracted by their own thoughts.

Just to be clear. I’m talking here about the importance of being positioned to win someone else’s attention. I’m not saying that you should never sit next to your boss. In other situations, that might be exactly where you’d want to be.

If she’s asks you to take the seat beside her, for instance, by all means do so. She may want to confer with you privately during the meeting. Or maybe she wants to signal her confidence in you. But when it’s important that she listen intently to you, set yourself up so you’ll have her attention before you even say a single word.

Additional Resources

- Jeanne M. Brett, Ray Friedman and Kristin Behfar, "How to Manage Your Negotiating Team," Harvard Business Review, 2009.

- Robert Cialdini, Pre-Suasion: A Revolutionary Way to Influence and Persuade, 2016.

- Donald Dell, Never Make the First Offer (Except When You Should), 2009.

- Elizabeth Long Lingo, Colin Fisher, and Kathleen L. McGinn, "Negotiation Processes As Sources of (And Solutions To) Interorganizational Conflict," Harvard Business School Working Knowledge, July 12, 2002.

- Michael B. Rainey, "Choosing Your Negotiation Site," Graziadio Business Review, Pepperdine University

- William Ury, Getting Past No, 1991.

- Michael Wheeler, "Assessment: What Kind of Negotiator Are You?," Harvard Business Review, February 5, 2016.

- Michael Wheeler, “Do you know where you should sit in a meeting”, LinkedIn Influencer, Oct. 17, 2016.

- • Michael Wheeler, “I Asked HBR Readers How They Negotiate—Here’s What I Found,” Harvard Business Review, June 3, 2016.