CLOSINGS

Dispute Resolution

Learning Objectives

Est. time: 20 min.

- Recognizing important differences between dispute resolution and deal making

- Selecting the appropriate dispute resolution process for the matter at hand

- Employing mediation skills in everyday negotiation

How you can participate

- Use the comment tool at the end of the module to add your insights and questions

- Engage with fellow learners and share your best practices

- Check regularly for comments from the creators of Negotiate 1-2-3

Introduction

Let’s begin with an example based on a real case and put you in the middle of it. You have been drawn into a bitter fight between your boss and Terry Worthen, a former colleague whom he fired eighteen months ago. Terry subsequently sued your company and your boss personally for age discrimination.

You have nothing to do with the circumstances that triggered Terry’s termination. You are friendly with each of these people, both of whom clearly like and trust you. In fact, each of them has privately asked for your help resolving this dispute before it goes to trial.

You hope, of course, that there could be a reasonable solution that would spare both parties the financial and emotional cost of a public trial. The parties themselves share that desire, as well, but they have very different views of what reasonable means. In your conversation with your boss, he asked you to persuade Terry to “drop this vindictive lawsuit.” When Terry phoned you several days later, he asked you to convince your boss to “apologize publicly” and to compensate him not only for his lost wages, but for his “pain and suffering.”

You separately told them each that you’re not comfortable getting involved, but each insisted that you’re the only one who can help. (It’s ironic that that’s the only thing they seem to agree on.) Obviously, you have no power to force them to come to an agreement, but each is still pressing you to make the other “be reasonable.” If they continue to ask, might you be willing to try to play an active role in resolving this dispute?

The Age-Old Discrimination Case

Some years ago, Harvard Business School Professor Jim Sebenius created a series of short dispute resolution cases with the considerable help of Marjorie Aaron, an accomplished mediator. Indeed, she mediated this case. The names of the parties have been changed to respect people’s privacy. Other than that, the facts that follow are unchanged. You’ll see the video interview in a moment, but here’s a little more background on the case.

The company provided secure data storage for small companies in its area. Its gross revenues were about $10 million annually, with annual profits around $1 million at that time. Terry Worthen, age 63, was a 15-year employee of the company, working as a commissioned salesman. When he was fired—ostensibly for poor sales performance—he was told that the company had a mandatory retirement age of 62.

Shortly after being terminated, Terry informed the vice president of sales that he had learned from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission that federal law prohibits mandatory retirement policies. Terry was then reinstated, but was warned that his performance would be closely monitored. A year later he was fired again on the grounds that his sales figures were lower than those of other salespeople.

Terry subsequently brought suit, claiming that he had been taken off his old accounts and given poor leads. He was convinced that he was set up to fail, and that his age was the real reason for his firing. The adversarial process got under way with the taking of depositions by both sides. The boss was outraged that Terry’s suit alleged “bad faith” and “intentional wrong doing.” Terry sought $1.8 million in damages, almost twice the two-year profits of the company.

Terry was represented by a lawyer who took his case on a contingency basis, so if he prevailed in court, Terry would have to pay a third of whatever judgement he was awarded to his attorney. (If he lost, he would owe nothing.) For the company, pretrial costs were already $35,000. Going to trial was expected to cost it an additional $40,000 to $50,000.

Nudged by the court, the parties agreed to try mediation. That is where Marjorie Aaron came into the story. Let’s see what happened next.

Fitting the Forum to the Fuss

There are many other forms of third party dispute resolution, beyond this kind of mediation. They fall along a spectrum ranging from simple facilitation—where someone convenes the parties and perhaps chairs a meeting—to binding arbitration where the intervenor has the power to declare who wins and who loses.

According to Frank Sander and Stephen Goldberg’s classic article “Fitting the Forum to the Fuss,” choosing the right process rests on diagnosing the obstacle that is preventing parties from reaching agreement on their own. In highly emotional disputes—like the one you just considered—the relationship-building skills of a mediator may be called for in.

Feelings may matter less in other instances, say where parties have an honest disagreement about the facts in question or their consequences. In those situations, an arbitrator may be called in to hear the evidence and make a ruling.

Judges have similar power, of course, but arbitration sometimes is preferable for both sides. For example, major construction contracts often require binding arbitration if disputes arise during the building process. (The construction firm and the owner might disagree about whether a modification of the plans falls within the originally quoted price or requires additional payment.) Arbitration may be much better for both parties than going to court for several reasons:

- The parties can select a neutral expert who specializes in construction and can make an informed decision, rather than rely on a generalist judge to decide a technical question.

- Arbitration cases can often be heard quickly so that construction can move ahead efficiently.

- Sometimes (but not always) arbitration can be cheaper if the parties agree to fast-track the process.

- Arbitration may be preferable if the parties don’t want business practices or trade secrets to be revealed in open court.

Sometimes the decision to bring in a third party isn’t made until a dispute arises. That can be problematic strategically, however. A party may hesitate to suggest mediation to a counterpart, lest that be misinterpreted as betraying a lack of resolve. Also, the parties may differ over which form of dispute resolution to choose or who should fill that role. (Sometimes in big cases, each party picks an arbitrator, and those two neutrals select a third.)

In ongoing business relations, it’s common for contracts to specify in advance that the parties will attempt to resolve possible future differences through mediation before taking them to court. There is controversy, however, over the legality—and certainly, the propriety—of so-called contracts of adhesion that attempt to prevent dissatisfied consumers from going to court and instead compel them to through an arbitration process tilted in favor the company.

Parties that have equal bargaining power sometimes come up with clever dispute resolution rules that are intended to discourage each other from using them. Years ago, Major League Baseball and the Player’s Association designed a process called Final Offer Arbitration. It governs contract disputes with players who have several years of experience, but who do not have enough tenure to be free agents with the right to negotiate with competing teams.

When a player and his team are deadlocked over salary, they must take their dispute to an arbitrator who specializes in these kinds of cases. Data about the player’s performance is presented, as is other information, then the player states a demand and the team counters with an offer. Here’s the twist: the arbitrator must pick one number or the other—he can’t split the difference.

Pause for a moment and consider why anyone would agree to such a process. After all, the arbitrator may regard the player’s demand as too high and team’s offer as too low. And yet he or she must pick one number or the other one, rather than impose the correct one.

The rule is intended to motivate both sides be more reasonable. When each party figures what to put on the table, they strive to put out a number that will look more plausible. As the parties negotiate in anticipation of this process, they should inch ever closer to one another. In theory, at least, they should reach agreement without ever getting the arbitrator involved.

In practice, though, the system doesn’t work perfectly. In the baseball context, both parties may be risk-seeking rather than risk-averse. A player who has already been offered $5 million may be willing to gamble that the arbitrator will give him $6. (If he loses, he’ll still be rich.) The team, thinking ahead to negotiations with other players, may prefer that the arbitrator make the award, even an adverse one, rather than setting a bad precedent themselves.

Finally, the dispute resolution process can evolve as it unfolds. A prominent Boston-based mediator was once called in to help resolve a dispute between partners in a big real estate deal. The construction project had gone well, but serious issues arose about managing the property or possibly selling it. The parties were in court to dissolve the partnership and divide the assets. The battle was over who would get what.

The litigants had already spent a combined $1 million on legal fees. Going to trial would cost at least that much, likely more. The presiding judge strongly encouraged them to try mediation rather than to continue to deplete the value of the contested resource by squandering still more money on legal costs.

The mediation proceeded in fits and starts over several weeks. The mediator met with all the parties together and then caucused privately with each one. Finally, though his efforts, they got to a point where, when the mediator added up the four demands, the total was only $250,000 more than the agreed value of the asset.

A quarter of million dollars is a lot of money but compared to what was at stake in this case, it was peanuts. Nevertheless nobody would budge. Each of the parties told the mediator that the number that they had given him was firm and final.

In frustration, hoping to shame the disputants into reasonable behavior, he said, “Okay. If that’s the case, how about you flip a coin for the difference.”

They all agreed!

Think about why. First, this ritual allowed everyone to save face. Nobody had to back down. Second, win or lose, it allowed each of them to be able to tell a great story about the day they flipped a coin for a quarter million dollars.

The mediator paired them off for a semi-final round. The coin was flipped and two of them advanced to the finals. It was flipped a second time and a winner was declared. He smiled broadly. The other three laughed even harder.

Battles of Principle?

Disputes arise not just between businesses and nations, but also among friends, family members, and neighbors. The conflict described just below was between condo owners in an apartment building. If you have already seen the Brinksmanship module in the Critical Moments unit, you may choose to skip it or read through it quickly to refresh your memory and see how it relates to closing negotiations, as well.

Example One

Some years ago, the Wall Street Journal reported on a battle between the owner of a New York co-op and his neighbors on the governing board. The board had passed a rule requiring all owners install bars on their windows to prevent children from falling out. The owner refused. He had no children and felt it was unfair (and pointless) to compel him to pay the $902 cost of installation.

Just as strongly, the board felt that its mandate must be honored. After all, children might visit the apartment at some point and might be sold to someone else with kids. Moreover, if the board made an exception in this case, other apartment owners might opt out as well.

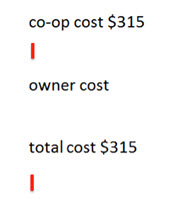

This owner ignored the bill, so the board hired a lawyer to write a “demand letter” warning the owner that if he did not pay, it would take him to court. The lawyer charged $315 for this service. Naturally, going to court would cost everyone much more.

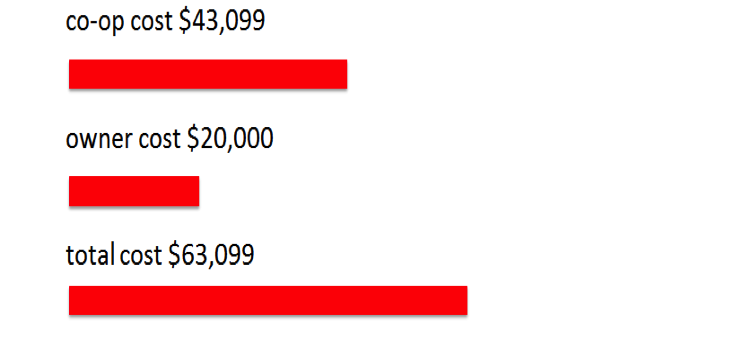

The owner still did not budge so the board took him to court, where the trial judge ruled in its favor. The process wasn’t cheap for either side, however. The owner paid his lawyer $5,000 and the board’s costs were almost twice that.

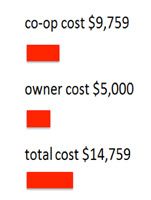

The owner didn’t give up. Instead, he challenged the trial court’s ruling in appeals court. This time he won, but the victory wasn’t cheap for him and, as before, the process was even more expensive for the board.

By this point the parties had spent a combined thirty times what would have been the cost of installing the window bars. The Journal’s account does not mention attempts of settlement or the use of a third party. But it’s likely others were concerned, since they would have to pay—in assessments—for the board’s costs however the case came out.

Perhaps one or more of the other neighbors tried to intervene, but if so, they weren’t successful, as you can see by revealing the hidden comments below.

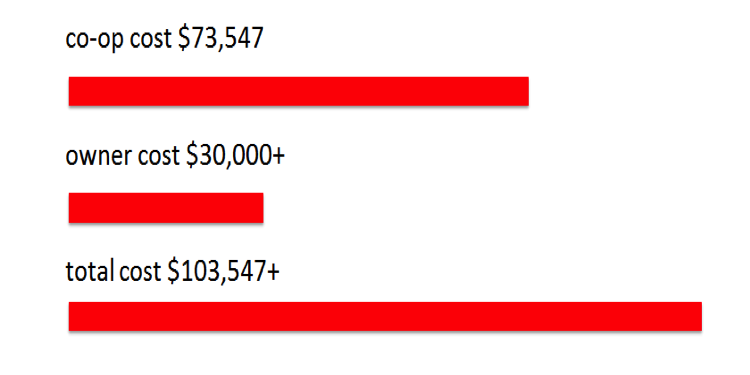

The board appealed the second court’s decision to a still higher tribunal and it reinstated the judgment that the owner must pay for and install the window bars. Now their combined costs had more than doubled once again.

This time the owner did not contest the installation order. But as you’ll see by clicking here, that was not the end of the dispute or of skyrocketing legal bills. You can see what happened by revealing the next set of hidden comments.

Now the parties found something else to fight over. The board sought to have the owner pay all its legal costs. The judge named a referee to decide that issue. He ordered the owner to pay $30,000 of the board’s fee, making the board swallow the balance.

When the disputants were done, they had spent combined more than one hundred times the amount originally in contention. Looking back, the owner said, “I’m a man converted. Anything you can possibly do to avoid a lawsuit, do it.”

By contrast, the board’s lawyer predictably had no second thoughts, “I think the expenditures here were appropriate and were pretty much kept to a minimum. . . Every step of the way they had an idea of what was going on. There were no surprises in this case.”

That seems like a dubious (and self-interested) claim. If at the outset, the board had a crystal ball and could have foreseen with perfect clarity that this minor dispute was going to cost them so much, would they really have plowed ahead? And what of the bystanders—the other owners who must foot the ultimate bill? Might one of them have found it wise to slip $902 in cash into the board’s mail slot, an anonymous payment of the recalcitrant owner’s bill? Doing so would have been a lot cheaper.

Those scenarios are all with the benefit of hindsight, of course. Yet if someone on either side had applied a bit of military strategy to the situation, the disaster might have been avoided. When United States Marines venture into dangerous situations with little time to plan, they always anticipate two important possibilities:

- What is the most likely thing that will happen?

- What is the most dangerous thing that could happen?

If just one person on the board had asked that second question, they might have recognized that the owner could prove to be as just stubborn as they were.

Perhaps at the outset they were right in retaining a lawyer to write a letter insisting that the owner pay his share. You might even argue that if the principle of not making any exceptions was worth defending, maybe going to court was necessary, as well. Most owners probably would have relented by then. But at some point—long before the costs rose to six figures—there should have been a Plan B that would have allowed a faster and far cheaper resolution.

Example 2

In the 1990s there was a business dispute between Stevens Aviation, a service and maintenance company, and Southwest Airlines, in which far more seemed at stake. The dispute easily could have escalated into a legal battle costing millions.

Stevens began an advertising campaign built around the slogan “Plane Smart” in its ads. A couple of years later, Southwest launched its “Just Plane Smart” campaign, prompting Stevens to claim trademark infringement. Instead of taking the airline to court, however, Stevens’ chairman Kurt Herwald proposed a different idea: He’d arm-wrestle Southwest CEO Herb Kelleher. The winner would get the rights, and the loser would have to donate to a charity of the other’s choice.

Kelleher lost the two-out-of-three match and sent a $10,000 check to the Muscular Dystrophy Association. Herwald, in turn, generously allowed Southwest to keep using its slogan. Both companies got great publicity from the stunt. Herwald said later that it was a factor in the subsequent threefold growth of his company’s business.

It’s estimated that 90 percent of lawsuits in the United States are settled before trial. (Actually, that number may be low.) But even when agreements are reached, the cost of disputes can be high for all concerned. There are transaction costs—legal fees and wasted time—of course. Beyond that, relationships can be stressed or even destroyed. Uncertainty about who owes what to whom can also hamper business planning and contaminate other transactions. Accelerating the resolution of disputes is thus almost always in everyone’s best interest.

Many of the same concepts and techniques that apply to deal-making also extend to resolving disputes. In both settings, parties need to consider their walkaway alternatives, weigh their full set of interests, and explore creative solutions. But there are critical differences, as well. In transactional negotiations, parties can usually walk away from a deal unilaterally. That’s often not the case with disputes (you can’t, on your own, decide not to be sued). So, in disputes, this a lack of control can frustrate each party and deepen their differences.

Moreover, disputes typically involve allocating loss. (In the windows case, either the owner was going to have to pay for windows he didn’t want, or the board was going to have change its policy.) Rather than being win-win, many cases like the windows story are lose-lose. Deals, by contrast, involve finding an outcome that benefits each side. Parties might bargain hard to get the larger share of that benefit, but that isn’t the same as suffering a loss.

Perhaps most important, perceived leverage in many disputes comes from being able to inflict pain or withhold valuable items. Party A may not like writing checks to their lawyer, but be convinced that by doing so, Party B will feel compelled to settle. But that second party may so resent the assault that they retaliate even more strongly. Like the litigants in the windows case, they dig themselves into a hole and then look for more shovels.

By contrast, wise negotiators like Herwald and Keller avoid sunk cost traps and instead transform disputes into deals to generate mutual gain.

Summary

Mediators have an adage that goes, “You know you’ve done your best work when the parties think that you haven’t done anything at all.”

The point is that if disputants believe that they found the solution without help, then they will own and implement it. And if the mediator is deft, perhaps without fully realizing it the disputants will have learned a bit about managing negotiation constructively from their example. They will have had an up-close demonstration of the importance of listening, exploring, and guiding the process with a light hand. If each side is alert, it may be able apply those lessons to settle future differences without the help of a third party.

Of course, neutrals can do some things more effectively than those with obviously partisan interests. A mediator who wins the confidence of disputants can encourage them to rethink their priorities. In private conversations with a mediator, disputants are more likely to reveal the issues on which they can compromise and others that are truly non-negotiable. A mediator can also offer a disinterested assessment of the situation and the likely consequences if the parties fail to agree.

Nevertheless, there are mediation approaches and techniques that negotiators with an obvious stake in the matter can emulate and adapt. Imagine two old friends, for example, one of whom is selling his family homestead to the other. Neither is rich, so they must both be mindful of money, but neither wants to take advantage of the other. Haggling is out of the question. What should they do?

One option would be for each of them to separately write down a walkaway price, on the understanding that they will split the difference if there is an overlap. If the most the prospective buyer is willing to pay is less than her friend, the owner, can accept, there won’t be a deal. Still both will know they each were willing to go to the limit for the other.

The overlap between negotiation and mediation skills is especially important dealing with colleagues in the workplace. To secure what you want and gain support for initiatives you favor, you will often have to resolve problems between other people over entirely different issues. The age discrimination case that began this module is such an example. The quiz put you in the position of someone who had nothing to do with Terry’s termination, but if a dispute like that is not resolved, it can negatively affect other parties and raise tensions within an organization. Getting involved may entail risks, but staying on the sidelines could be even more perilous.

Some years ago, David Lax and James Sebenius wrote a landmark text that is still in print, The Manager as Negotiator. There is still space on the bookshelf for a companion, The Manager as Mediator.

Resources

Deborah Kolb and Jessica Porter, Negotiating at Work: Turn Small Wins into Big Gains, Jossey-Bass; 1st edition, 2015.

David Lax and James Sebenius, The Manager as Negotiator, Free Press, 2011.

Frank Sander and Stephen Goldberg, "Fitting the Forum to the Fuss: A User-friendly Guide to Selecting an ADR Procedure," Negotiation Journal, January 1994.

Jeswald Salacuse, Real Leaders Negotiate!: Gaining, Using, and Keeping the Power to Lead Through Negotiation, Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.