CLOSINGS

Persuasion

Learning Objectives

Est. time: 20 min.

- Understanding the role of persuasion in the negotiation process

- Seeing how people may be influenced to make choices in their own interests

- Distinguishing permissible persuasion and unethical manipulation

How you can participate

- Use the comment tool at the end of the module to add your insights and questions

- Engage with fellow learners and share your best practices

- Check regularly for comments from the creators of Negotiate 1-2-3

Introduction

From start to finish, persuasion is at the heart of negotiation. Even before the process begins, parties may have to be convinced to come to the table. Then when negotiation is underway, persuading counterparts of your trustworthiness is essential. And to close a deal at the end, other parties must be convinced that your proposal is better than what they can get elsewhere.

This module briefly summarizes important psychological research about persuasion. We’ll consider decision making—saying yes or no to a specific proposal—and how people regard one another more generally. A vast amount of work has been done in this realm. We can only sample a small portion of it. (The resources listed at the end of the module will give you a much deeper understanding of persuasion.)

Right now, as you go through the material in this module, consider it from two complementary points of view:

- One is outward facing: What can you do and say to increase the probability that your counterpart will respond to you the way you would like?

- The second looks inward: What influences your own choices in negotiation—and do they sometimes subvert your own interests?

We’ll start with a short activity. If your birth year is an odd number (such as 1981), take Version A. If you were born in an even-numbered year, please take Version B. Click below to make your selection.

The next section of this module explains what the quiz reveals about persuasion. We’ll start with the first questions you answered the one about the Center for Disease Control scenario, and the other about finding or losing money). A bit later we’ll get to the sentence construction quiz.

Persuasion Science (in a nutshell)

Negotiation is a matter of give and take. To get what you want from another party, you typically must grant something of value to them. With any proposal you make, the benefits must outweigh the costs. Likewise, it will be acceptable to the other side only if it is also net positive for them, as well. It turns out, however, that many people aren’t very good at making those calculations. At the very least, they aren’t consistent.

In the quiz you just took, you had to make a hard choice about which plan the Centers for Disease Control should implement in response to the outbreak of a deadly disease. The great majority of people who took Version A of the quiz picked the first plan, but almost 90 percent of people who took Version B chose the second, even though the two options were exactly the same for everyone!

How could that be? You were asked to take Version A or B, according to your birth year. But it’s not that people born in even years think very differently than those born in odd ones. It’s only because the wording of the questions everyone saw varied somewhat. Here are both versions:

VERSION A

Plan A will result in 200 people being saved.

Plan B offers a one-third chance that 600 people will be saved and a two-thirds chance that noone will be saved.VERSION B

Plan A will result in 400 people dying.

Plan B offers a one-third chance that no one will die and a two-thirds chance that 600 people will die.

Notice that the consequences are the same for the 600 afflicted people. Only the emphasis changes. In Version A, Plan A speaks of 200 people being saved, while Version B describes 400 people dying. When saving lives is cued, people gravitate towards that option. When death is featured, people avoid it. But the basic equation (200 survivors and 400 fatalities among the 600 patients) is the same either way.

It’s sobering to realize that life-and-death decisions can be swayed by the wording of the choice. It’s due to a common trait called “loss aversion,” first identified years ago by the late Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman (author of the much more recent Thinking Fast and Slow). They developed the Disease Control scenario (and many others) for their research on decision biases that can tilt our thinking in lots of contexts. (Incidentally, from a purely “rational” point of view, all four options—A and B for both versions—have the same expected value: 200 people will live; 400 will die)

But how do these findings relate to negotiation? If you want to encourage someone to say yes to an offer, emphasize how doing so will help will help them avoid a loss. For example, let’s say a power company does energy audits for homeowners. When the survey is done, which statement is more likely to persuade people to purchase more insulation, number 1 or number 2?

- If you re-insulate your home, you will save $100 a month.

- If you fail to re-insulate your home, you will lose $100 a month.

Remember, losses count more psychologically than do equivalent gains, so the second formulation will garner more sales. But there is a way to increase the heft of potential gains.

Once again, the second question in the quiz was different in Versions A and B. Those who were born in even-numbered years were asked, which of these would make you somewhat happier?

Scenario X: You are walking down the street and find a $20 bill.

Scenario Y: You are walking down the street and find a $10 bill. The next day, as you are walking down a different street, you find another $10 bill.

A large majority of respondents say that the second option—finding $10 bills on successive days—would make them somewhat happier than simply finding a $20 bill once. That may not seem to make sense in economic terms—you get twenty dollars either way—but Scenario Y enables you to have two bursts of unexpected happiness.

By contrast, those born in odd-numbered years were asked about two options, both with a downside: Which of these would make you somewhat unhappier?

Scenario X: You open your wallet and discover you have lost a $20 bill.

Scenario Y: You open your wallet and discover you have lost a $10 bill. The following day, you lose another $10 bill.

Once again, the economic consequences are the same, but respondents to Version B strongly prefer being done with the loss of twenty dollars all at once.

On the basis of such studies, Harvard Business School Professor (and decision-making authority) Max Bazerman advises that, in crafting proposals, negotiators should “aggregate the other party’s losses and disaggregate their losses.” Bundling the losses into one item—big as it may be—is better than itemizing particular costs so that the other party doesn't feel that they are dying the death of a thousand cuts. By contrast, disaggregating the benefits—enumerating each and every one—generates a series of pleasant expectations.

Psychologist Robert Cialdini’s Yes: 50 Scientifically Proven Ways to be Persuasive catalogs techniques for swaying people’s choices. He would build on Bazerman’s advice by adding the importance of explicitly stating the value of each thing that you offer. Let’s say a software company is willing to give away a computer security program in hopes of attracting new business. That might be smart advertising, he says, but don’t describe the product as free.

“If you fail to point out what it would cost customers if they had to pay for it themselves, you’re losing out on an effective way of positing your offer as value and significant. After all, if you write down ‘free,’ numerically the number is $0.00—not the message you would want . . . Much better if the offer reads: ‘Receive a $250 security program at no cost to you.’”

Cialdini also notes research that demonstrates how powerfully a modest request can lay the foundation for succeeding with a much bigger ask. He describes a study by Johnathan Freedman and Scott Fraser who wanted to see what it would take to persuade homeowners in a fancy neighborhood to allow the placement of a six-by-three-foot sign stating DRIVE CAREFULLY on their front lawns. And the sign was unsightly. Yet they ultimately were able to get 76 percent of the owners to agree.

What was the secret of their success? Two weeks earlier, they had gone to the same households and asked residents if they would place a small, inconspicuous sign in their windows that said BE A SAFE DRIVER. Almost everyone agreed. According to Cialdini, once they had committed themselves to a worthy cause, it was much harder for them to refuse the more onerous request.

It’s fair to ask whether these techniques are manipulative. In a literal sense, undoubtedly yes, as they are aimed at influencing another person’s decision. But whether doing so is unethical isn’t as clear-cut. There is unresolved controversy over the growing use of cognitive bias findings in formulating public policy, notably the so-called “status quo” bias.

For example, some European countries give citizens the option to donate their organs when they die. Where that’s the policy (in Denmark, the Netherlands, Germany and the United Kingdom), on average 15% of the population opt into the program. By contrast seven other countries (among them, Austria, France, and Sweden), presume that their citizens will donate, but give people an option to opt out. On average more than 95% stay in. Either way, the status quo carries great weight (as does social proof, the follow-the-crowd tendency).

The point is that whether in negotiation or in any other setting where decisions must be made, the way in which the choice is posed may well affect how people will respond. It does not seem inherently wrong to frame a proposal in a way that is beneficial to oneself, provided—and this is a big caveat—that information about the consequences has not been distorted or withheld. If that is valid, however, we must anticipate that others may permissibly frame their proposals so that we view the choice in a light that most favors them. It is our responsibility to consider whether choosing another perspective would lead us to a different conclusion.

Bear in mind, as well, that people’s impressions of favors depends on whether you are the giver or the receiver. Moreover, those impressions evolve over time. Cialdini cites researcher Francis Flynn who has found that “immediately after one person performs a favor for another, the recipient of the favor places more value on the favor than does the favor-doer. However, as time passes, the value of the favor decreases in the recipient’s eyes whereas for the favor-doer, it actually increases.”

As offers and counter-offers go back and forth, be prepared to resist your counterpart’s frame. I once witnessed a negotiation between a car salesman and a potential customer. They seemingly had agreed on a price, but at the last moment the salesman tried to add another item to the cost. It was the so-called “doc fee,” an extra charge of $300 for the paperwork that the dealership has to do to complete the transaction. The customer refused to pay, so the salesman brought him to the manager to work things out.

The conversation went something like this.

Customer: We agreed on the price. I’m not paying a dollar more.

Manager: It’s a standard charge. Every dealer does it.

Customer: I don’t care. We shook hands. A deal is a deal.

Manager: If you don’t pay the $300, it will come out of the salesman’s pocket.

The manager and the customer were standing toe-to-toe, at that point. The salesman likely hoped that the customer, already committed to paying five figures for the vehicle, wouldn’t let $300 get in the way of sealing the deal. He was playing the loss aversion card, two of them in fact: the customer’s loss of the time already spent negotiating and the anticipated pleasure of having a new car. On top of that the manager was asking the customer to be fair to the lowly salesman.

Take a few seconds to think about what you would say under those circumstances, then click here to see how this customer responded.

Manager: If you don’t pay the $300, it will come out of the salesman’s pocket.

Customer: Yeah, but if I do pay, the $300 will come out of my pocket.

Perhaps you came up with an even better retort, but this one worked. The manager waived the doc fee. But note what the manager was trying to do (and which may have worked with other customers). He was trying to persuade the customer to pay the extra amount—not to him or to the dealership—but to the salesman. If you stop to think about it, the manager was asking the customer to be more generous towards the salesman than he himself was willing to be!

We have looked at loss aversion and, in passing, the status quo bias. Others cognitive biases come into negotiation, as well. For example, most of us are overconfident about the accuracy our judgments. If we’re asked where Coca-Cola ranks on the Fortune 500 list or the number of grandparents in the United States, we know our guesses could be wrong, but we wildly underestimate how wrong we often are.

Likewise, in negotiation you need to make judgments about other party’s perceptions and values. Your reading of the other party will establish the baseline for formulating your strategy to reach agreement. Beware of being overly confident that you’re addressing their true interests. Constantly test your own assumptions about other parties and imagine other possibilities.

When issues of principle are involved, a big mistake that you can make is framing your argument in terms of your own values, rather than those of your counterpart is a big mistake. Sociologists Robb Willer and Matthew Feinberg presented liberals and conservatives with one or two messages supporting same-sex marriage. One version emphasized equal rights, a principle of fairness prized by liberals. The other described same-sex couples as “proud and patriotic Americans” who “contribute to the American economy and society.” As you might expect, liberals supported both messages equally. With conservatives, however, including the patriotic phrases made a positive difference.

In hindsight, that effect may not seem surprising, but in a parallel experiment Willer and Feinberg created a contest in which liberals could win a cash prize for writing the best argument for persuading a conservative to support same-sex marriage. Only nine percent of liberals made statements that appealed to conservative values, while 69 percent made arguments that were confined to their own values. (Lest you think that the researchers were partisan themselves, other studies they did on increasing military spending—a priority of many conservatives—showed exactly the same kind of myopia.)

Here’s the punchline: a persuasive argument must appeal to your counterpart’s interests and values, not your own. Reasons that you find compelling may be irrelevant—even repugnant—to them, as research by Matthew Feinberg and Robb Willer have described in their article “From Gulf to Bridge.”

Shaping the Relationship

Here’s a challenge. You are a skillful negotiator. It’s a hot summer afternoon and you’re on a crowded city busy inching its way along in rush hour. Every seat is taken and you’re standing, as are lots of other people. How do you get to sit?

Let’s make it harder. You’re carrying nothing of value. No money. No candy. No magazine. You have nothing to trade. So, what do you say to the person right in front of you? You might ask, “Could I have your seat?” but what’s the chance the answer will be yes? Ten percent? A little better than that? Or even worse?

Whatever the odds are, adding seven words—one in particular—that will significantly increase your chances. Click here to see the full sentence.

“Could I have your seat, because I would like to sit down?”

Here’s why that would help. Harvard psychologist Ellen Langer did a study years ago in which her assistants asked to cut in line to make copies. Those were days when copiers were rare devices and they worked more slowly, so people often waited for their turn. People may also have been more accommodating back then, as 60 percent of the time those who had been waiting allowed the assistant to go first. The success rate shot up to 94 percent when people added the phrase “. . . because I’m in a rush.”

But the most startling result came when people simply said, “Excuse me. I just have five pages. May I use the Xerox machine because I have to make some copies?” Those seven words are redundant. They provide no further justification for jumping the line. Even so, 93 percent of the people let the assistant cut in. The effect has been replicated in many experiments since the original one, including studies on subways and buses, as we considered here.

Langer concluded that the key word in all the additional phrases is because. When you ask people for something, they want to hear a reason. It’s a matter of ritual, a form of respect. According to the research, the reason doesn’t necessarily have to be a good one, at least when the request is for a small favor. The more compelling the justification, of course, the more likely you are to get a yes.

Be careful, however, not to build too long a list, of course. If there is one—and only one—good reason for your counterpart to accept your offer, stick with it. If you add less plausible claims, the other person will poke holes in them and miss the main point.

Your actions—not just your words—can make you more persuasive. Cialdini explains how the norm of reciprocity often causes people to overpay when they return a favor. Social psychologist Dennis Regan did a much cited study in which people completed a questionnaire. Seated near them was another person that they assumed was another subject doing the same task, though he really was an assistant to the experimenter. Midway through the test, that second person left to get a Coke and, without being asked, brought back another one for the subject.

The real test occurred after the forms had been filled out. The assistant mentioned that he was selling raffle tickets as part of a fund-raiser. Subjects who had been given a Coke bought twice as many tickets as did those in the control group who didn’t receive a gift. And what the Coke-receivers paid was much more than the cost of the soda.

So again, it’s a common practice. If you have a nice car and go back to the dealer for service, there’s probably a waiting room where you were treated with coffee and snacks. It’s a thoughtful gesture, perhaps, but it’s also one that is likely to make you a repeat customer. And the cost is likely somewhere in the bill. So again, it’s appropriate to ask if the practice of unilaterally granting small favors is manipulative. There’s a sound argument that astute customers can take their business wherever they want. If there’s another service station nearby that doesn’t have the same perks, but does equally good work at a lower price, they can carry in coffee in their own travel mugs. A more subtle, yet more troubling moral concern, is the potential impact on people who give small favors as a tool for getting bigger ones in return. It’s a matter of degree, of course, but it free rides on the coattails of genuine acts of kindness done with no ulterior motives. And that, in turn, could prompt cynicism and distrust.

Of still greater concern is recent research that indicates bodily mimicry can enhance persuasiveness and likeability. Simultaneously copying another person’s movements and expressions is obvious and annoying. But waiting a couple of seconds apparently has positive effects. Duke University psychologists Robin Tanner and Tanya Chartrand had subjects try out a new sports drink and then answer several questions about it. Those who (unknowingly) had been mirrored were significantly more likely than the control group to say that they would buy the product and that it would succeed on the market. Other studies have shown similar effects. (The Negotiating How to Negotiate module in the Openings unit includes videos of different negotiators whose posture and actions mirror one another, probably without them being aware of it.)

Mirroring is taught in many sales training courses, so perhaps we shouldn’t be alarmed. (Or if we are, there may not be much we can do about it.) But it is different from other persuasion techniques we’ve covered (such as how a proposal is framed or even whether your car dealership gives you “free” coffee). It raises similar questions about manipulation, but in this instance the actions are invisible—deliberately so. Because there is no cue, you don’t have an opportunity to double-check your reasoning or to rethink how grateful you should be for a small favor. Perhaps the best any of us can do is to slow down our decision-making process when important issues are a stake to see if any external factors may be erroneously tilting our choices.

As for using the technique yourself, consider the downside. Devoting your attention to exactly when and how to copy someone else’s movements—and whether the stratagem is working—necessarily takes you away from the important substantive work of trying to craft a creative agreement.

Being Persuaded Yourself (Without Knowing It)

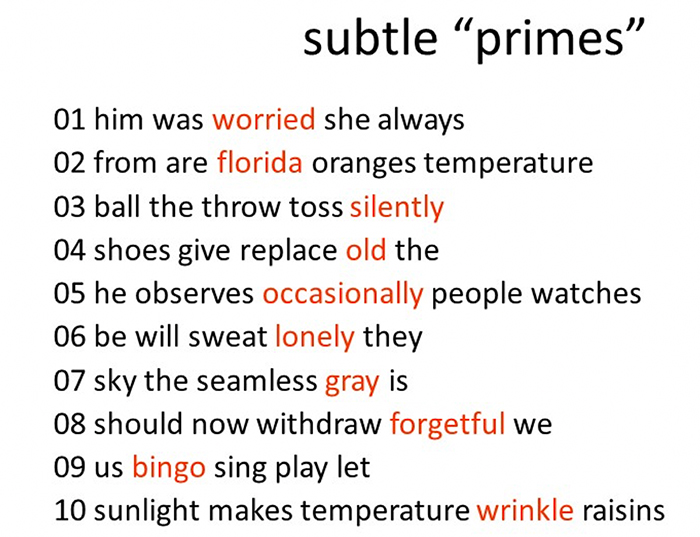

At the beginning of this module, you took a short quiz. Some of Version A’s questions were different from those in Version B, but everyone saw the same question three (the one that asked you to make a four-word sentence out of random sets of five words each). It was not a test of your creativity or your fluency. Instead, the question was there to introduce you to psychological primes, words that can affect your mood and behavior. The question is from an experiment by John Bargh of New York University and his colleagues.

Here’s the list again, with particular words highlighted. Do you see the pattern?

For many people, the words subtly suggest old age and weariness. They had a powerful, unconscious effect: subjects in Bargh’s experiment walked out of the lab more slowly than they had walked in! A parallel experiment demonstrated how subliminal cues not only affect us physically, but socially as well. Here the researchers primed two groups with different sets of words. One group saw these: aggressively, bold, rude, bother, disturb, and infringe. The second group read these terms: respect, considerate, appreciate, patiently, yield, polite, courteous.

Subjects were then instructed to go to another office to pick up the next assignment. (A stooge was in the way, casually chatting with the administrator.) People in the first group—who had seen words like aggressively—interrupted the conversation in five minutes, on average. But 82 percent of people in the second group never interrupted in 10 minutes. And all these subjects were from New York!

When you go to a meeting or a negotiation, you will hear snatches of conversation or bits of a story on the radio along the way. No single word is likely to change your mood, but the general tone of what you hear potentially tilts your outlook and behavior. So do the random thoughts that pass through your mind. Most certainly, so does what we hear during a negotiation session. There is no way to backtrack and find the source of all your feelings and responses, but it pays to be mindful of your disposition and whether it serves your interests. Moreover, according to Robert Cialdini’s book Pre-suasion, there are things that you can do or say before you make a request or float a proposal that can increase the likelihood you’ll get the answer you want.

Question four in the quiz illustrates ways in in which you can persuade yourself to be a more effective negotiator. It’s based on an experiment by Adam Galinsky and his colleagues. They told subjects to write quick notes to themselves before doing a negotiation simulation. One group got the instruction that you saw if you took Version A of the quiz. The second group received the instruction that you read if you took Version B.

Version A encourages positive behavior. It focuses on aspirations, hopes, and accomplishment. It reads:

Imagine that you have an important negotiation coming up. Take a moment to think about the kinds of negotiation behaviors and outcomes you hope to achieve. Now, jot down a few reminders so that you can make them happen.

Version B is more defensive. It focuses on safety, risks, and responsibilities. It reads:

Imagine that you have an important negotiation coming up. Take a moment to think about the kinds of negotiation behaviors and outcomes you hope to avoid. Now, jot down a few reminders so you can prevent them from happening.

As you’d expect, the positive “promoters” made bolder demands than did the more cautious “preventers,” as Galinsky’s team labelled the two groups. While the former concentrated on what they could accomplish, the latter thought about how they could fail. But there was a bonus: when promotion-primed negotiators were primed up against one another, they created far more value than did pairs of prevention-primed people. Those in the latter group tended to accept anything that met their minimum needs, while the promoters pushed harder for their real priorities instead of just compromising. As a result, they were more likely to spot mutually beneficial trades.

Summary

Former New York City detective Dominick Misino has been conducting high-wire hostage negotiations since the 1970s. He has a natural gift for connecting with other people, even in dire situations. His frequent successes are even more remarkable considering how little he has to offer someone in return for a peaceful surrender. He can’t promise clemency or a getaway car. His main resources are his own presence of mind and emotional attunement.

“Top negotiators are excellent listeners,” he says. Misino is always asking questions, trying to build rapport. When he asks hostage takers to tell their side of things, he gets back an earful. For example, “I hear every instance of when the other guy has ever been wronged.” When they tell him that they’ve never been cared for or that they’ve been framed, Misino is nonjudgmental. “The way I look at it, all of it is true—to him. And that’s what matters.”

Misino also listens to himself. He says that hostage negotiators must be aware of the “noise” in their own minds. “Believe me, even if you don’t know what’s going on inside your head, the other guy will,” he notes. “You need to know your hot buttons and limitations.” Early in a conversation, he typically asks if the person wants to hear the unvarnished truth. The answer is almost always yes. (When somebody is in a standoff with police snipers, he observes, “Who in his right mind would have wanted to be lied to?”) But then Misino will attach a condition. The guy has to promise not to hurt anyone even if he hears things he doesn’t like. Nine out of ten times, such promises are kept. “These people may be the outcasts of society,” he says, “but they do have a code of honor.”

To deepen trust, Misino adds, “You use every possible opportunity to agree with your adversary and to get him to agree with you.” He deliberately uses the plural pronoun (as in “Wecan work this out”), to “alleviate the bad guy’s isolation and paranoia.” In this context Misino doesn’t comment. He doesn’t argue. Instead, he just takes one simple step after another without explaining where he is headed—though he knows that surrender is the only option. Misino’s key insight about the whole process is stated so simply, it’s easy to slip right past it, so it’s italicized here for emphasis: “A successful negotiation is a series of small agreements.”

For him, persuasion isn’t about carrots and sticks, charm, or bluster. It’s about relational understanding. By being respectful, he elicits respect in return. By listening closely, he teaches the other person to listen to him. In the end, Misino can only offer respect, empathy, and safety. Surprisingly, that often proves sufficient.

Resources

John Bargh et al, “Automaticity of Social Behavior,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 71, no. 2 (1996): 230-244.

Robert Cialdini, Influence: The Science of Persuasion, Harper Business; revised edition, 2006.

Robert Cialdini, Yes: 50 Scientifically Proven Ways to be Persuasive, Free Press, 2009.

Robert Cialdini, Pre-Suasion: A Revolutionary Way to Influence and Persuade, Simon & Schuster; reprint edition, 2018.

Matthew Feinberg & Robb Willer, “From Gulf to Bridge,“ Personality & Social Psychology bulletin, 41 (12) October 2015.

Jay Conger, “The Necessary Art of Persuasion,” Harvard Business Review, May-June 1998.

David DeSteno, The Truth About Trust, Plume, 2015.

Adam Galinsky et al, “Promoting Negotiator Success: The Role of Regulatory Focus in the Distribution and Efficiency of Negotiated Outcomes," SSRN Electronic Journal, October 2004

The Essentials of Power, Influence, and Persuasion, Harvard Business Review Press, 2006.

Daniel Kahneman, Thinking Fast and Slow, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013.

“Richard Shell, The Art of Woo: Using Strategic Persuasion to Sell Your Ideas, Penguin Books, 2008.

Zachery Tormala and Derek Rucker, “How Uncertainty Transforms Persuasion,” Harvard Business Review, September 2015.

Chris Voss, Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On It, Harper Business, 2016.

Michael Wheeler, The Art of Negotiation: How to Improvise Agreement in a Chaotic World, Simon & Schuster, 2013.